Chapter Two: Abundant Sincerity

When I first ran for office I saw myself as a savior.

When asked why I was running, I'd answer, 'to do good for

people'; black people, white people, farm workers, children

born blind or with no hands. "You can't say he's not a good

guy," my wife said. (She was in the room and volunteered the

comment while listening to me toot my horn giving David

material to incorporate into this manuscript.) It felt good to

imagine myself as a savior. I knew that in the time allowed me

I couldn't remake the world, but this was an intellectual

supposition: that I wouldn't accomplish all the things I set

out to do in office. A part of me still believed I could maybe

save the world...just as most of us partially, I think, live

and act as if we were going to live forever.

The same force in me which believed in my omnipotence

slowly pushed me into politics. In the early years my vigor

was stronger, like that of the young man who jumped on his

horse and gallantly rode off in all directions simultaneously.

I believed that all things were possible but I didn't do much

about it.

My active involvement came about gradually, for several

reasons. Partly, at first, I was afraid. I'd been badly

defeated when I ran for Napa High School student body

president. There were three in the race. The tally was 500 for

the winner, 320 for second place, and 91 for me. In college I

held no office--not even in my fraternity. So I didn't have an

image of myself as a winner. I didn't want to admit I wanted

something I might not be able to get. I'd never been a leader

with a real title, or brought myself up before people and

asked for their official approval. Also, I had the problem of

having a strong family background of Republicans, when my own

predisposition leaned fairly strongly Democratic. My father, a

lifelong Democrat, switched to Republican a year before his

death in 1953. My brother and law partner was a Republican, my

uncle was the strongly Republican State Senator Nathan Coombs,

and my grandfather was a Republican and had been Speaker of

the Assembly in his own legislative career (then later was a

Congressman and an Ambassador). I spent my first seven or

eight voting years as a registered "Decline to State". I saw

both political parties as a little phony and felt myself

"better" than either--but finally, when in 1952 the Democratic

Party chose Adlai Stevenson as its standard bearer in the

presidential race, I decided they were good enough for me and

"came out" Democratic.

Adlai Stevenson and the 1952 presidential election was

the first step but it wasn't until 1954 that I actually got

involved in politics. The precipitating event was a

conversation which took place when my wife and I were

entertaining another couple one Saturday night. (All of us

were right around the same age--32--at that time.) My friend

Don Searle and I were exposing our customary know-it-all

attitude, belittling those in power and issuing enlightened

judgements. We were talking about Eisenhower and the Red-

baiting Senator Joe McCarthy.

Don said Ike didn't have any guts or he'd silence McCarthy.

I said, Ike's just inept, he doesn't realize the harm

McCarthy's doing and he doesn't realize how the moral force of

the Presidency could be used to put him down.

We agreed that whether Ike lacked guts or was inept, the

result was the same, McCarthy was allowed to continue his Red-

baiting unchecked, and innovators of any kind ran the risk of

being branded Communist. New ideas of any kind were likely to

be lost to us--the accepted dogma of the day was all that

would be considered safe--"The Russians are coming and they're

coming with Big Guns and if you sound a little like a Russian (and

here's how they sound) you might be one; get your 'new ideas' later,

what we need now is more Americanism." Don and I deplored the

McCarthy situation and almost revelled in how right we were and how

wrong they were. Janet, bored with all our yak (and this

wasn't the first time) said "I'm tired of hearing you guys

wallow in your own sanctimonious preaching, why don't you do

something about it instead of just acting superior and talking

to each other."

In my defense I may have retorted something like, 'right

thinking must precede right action', but Janet's words were

true and as I look back on it now I think they triggered a

real participation in politics. Within six weeks I'd attended

my first Democratic Club meeting, gotten myself elected

treasurer, and gotten Don to attend the next meeting with me.

From 1954 to 1960 I was an active persistent Democratic

Eager Beaver in pursuit of political perfection. I did all the

usual chores, from helping to register Democrats, to bumper

sticking cars, to licking and sticking envelopes. With others

I challenged local Republicans to debates and tried to lead on

local issues. Starting in 1954 I worked in the campaigns of

many aspiring Democratic candidates.

For many years California had been dominated by the

Republican party. In fifty years there'd been only one

Democratic governor. In periods of reform liberal Republicans

like Hiram Johnson and Earl Warren had captured the State

(i.e. the Governorship). In much of the state, Democratic

leadership was dormant, docile, and inarticulate. Democrats

were critical of Republicans but they had no positive

philosophical approach of their own. Those of us who became

active in the fifties had some definite ideas which we

demanded to see expressed within the party. For example, a

tax policy based on ability to pay, conservation of energy and

nature, and equal opportunity in employment, education, and

housing. Decadent party leadership was being pruned away.

In the county elections of '54, '56, and '58 we activists chall-

enged the old guard and generally won enough seats on the

County Democratic Central Committee* to take control. A few

old guard members changed their spots and worked with us,

others dropped by the wayside--and a few actually re-

registered as Republicans.

It was a time of great satisfaction. We were working hard

to build a party which meant something philosophically and

also had political clout. Things were going right and it felt

good. In the '58 elections, Democrats captured both houses of

the State Legislature (along with most statewide offices,

including Governor) and in my area elected a Democratic

Congressman. Having been his campaign chairman in Napa County,

I became one of the county's major Democratic leaders. I was

on my way into the swim of things. I'd lost the youthful

arrogance that had made me reluctant to join either side, and

though I probably didn't think of it very often, I'd given up

some of my freedom to question everything by becoming an

active Democrat. Because of my success in leading our

Congressman's campaign. and in other local efforts, I felt

_______________________

*In California the County Democratic Central Committee,

composed of from 20-30 members, is the official party

organization. Members are elected at general elections for two

year terms. Sometime they have been so moribund as to have

many vacancies as a result of apathy, people not even running

for the office. Their actual governing power is normally

almost nonexistent except that they can be used as a platform

to articulate political ideas, ideals, programs. Central

Committees also are often involved in fundraising.

ready to try for office myself. Unfortunately, I made a mistake

in timing. In 1960 instead of running for a relatively safe

Assembly seat, I chose to take on our Democratic Assemblyman in

his bid for the State Senate. The Assembly seat he vacated

would have been an easier race. He'd been in office for eight

years and comparatively speaking, I was an unknown. I thought I

was justified in trying to oust him because he'd been an old

guard Democrat, failing to lead effectively in party reform--I

thought I'd do more good in the Senate, provide better

leadership, and was just better qualified. However, he defeated

me in a close but decisive election.

I did make a credible showing, carrying Yolo County by 400,

losing Napa by 4,000.

It hurt to lose, even if my friends did say 'the masses

are asses'--it was my own failure to convince them that I was

the wiser choice of candidates. I'd been a little greedy and I

knew it. It was a personal defeat for me and a defeat for

liberals in general, and I'd pretty clearly become the

candidate of innovation, speaking out against the death

penalty, criticizing tax loopholes for corporations, and taking

progressive stands on more obscure local issues. I wondered a

little if I hadn't been afraid of success and deliberately

bitten off more than I could chew. I could've run for that

Assembly seat and won. I don't regret losing now, but it sure

hurt then.

I did make a credible showing, carrying Yolo County by 400,

losing Napa by 4,000.

It hurt to lose, even if my friends did say 'the masses

are asses'--it was my own failure to convince them that I was

the wiser choice of candidates. I'd been a little greedy and I

knew it. It was a personal defeat for me and a defeat for

liberals in general, and I'd pretty clearly become the

candidate of innovation, speaking out against the death

penalty, criticizing tax loopholes for corporations, and taking

progressive stands on more obscure local issues. I wondered a

little if I hadn't been afraid of success and deliberately

bitten off more than I could chew. I could've run for that

Assembly seat and won. I don't regret losing now, but it sure

hurt then.

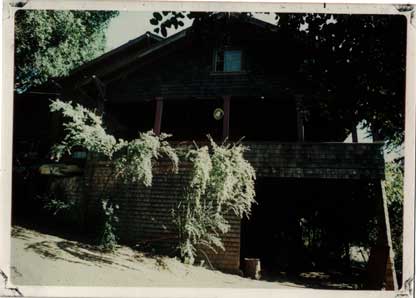

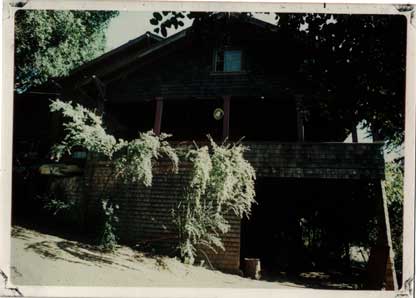

In 1958 we lived in a big, old, rustic but charming ranch

house perched among live oak trees on a valley hillside east of

Napa. It was owned by my uncle, who was incidentally my senior

law partner in "Coombs, Dunlap, and Dunlap", and a Republican

State Senator.

In 1958 we lived in a big, old, rustic but charming ranch

house perched among live oak trees on a valley hillside east of

Napa. It was owned by my uncle, who was incidentally my senior

law partner in "Coombs, Dunlap, and Dunlap", and a Republican

State Senator.

The ranch had a high-up front porch with a

beautiful view (all the way up the valley to Mt. St. Helena).

It held fifty to a hundred guests and only creaked a little

under their weight. Yellow rose vines clung just over the porch

railing, and, a hundred yards off were all varieties of fruit

trees, untended but still thriving. The livingroom was also

big, warmed by wood floors walls, and ceilings, a protruding

fireplace with nooks on each side, and window seats under the

windows to the porch. With people crowded in and standing room

only a hundred people could listen to a speech.

Over a good many years Janet and I worked together

building my career. Sometimes we just gave large social parties

which I wouldn't have then admitted had any political

significance. Later many of our parties at the ranch were given

for specific partisan purposes, even large fundraisers like the

cocktail party for the late Congressman Clem Miller. The day

before that party we realized we didn't have enough furniture

and for 8 dollars bought a used couch which was a horrible red

and gold. For less than 2 dollars we purchased a can of black

fabric paint (Janet knew you could do this, I'd never heard of

it before)--it was called 'Fabspray' and it made the couch

really. . .well, not too bad. But we weren't sure how dry it'd

be for the party.

The next day I remember greeting guests on

the front porch and seeing a lady in a fancy hat and an elegant

white knitted dress, a gussied-up person who cared about how

she looked. If I'd had a chance to warn Janet to steer her away

from the couch I would have, but, as it turned out a little

later we both spotted her sitting there, and there was nothing

either of us could do--only when she got up about 20 minutes

later were we sure the paint was dry.

We were a good political couple. Janet could be more

gregarious than I. She was sincere and charming, I was just

sincere. But together we had a kind of crazy dedication and

willingness to try which made things work.

Being more sincere than charming, I had some political

convictions which I thought needed airing in staid old Napa. I

belonged to an ad hoc group which recognized that Napa was a

"lilywhite town". For instance, there were 300 blacks employed

at the Napa State Hospital located on the southern border of

the city, and none of them lived in Napa, all lived in Vallejo or

Fairfield. This was maybe 1963, about 100 years since the end of

the civil war.

Our group sponsored a public forum on the

subject. Afterward we got 400 people to include their names in

a full page ad in the Napa Register saying we as citizens would

rent or sell our homes to anyone who had the money to buy them

regardless of race, color, or creed. This is of course the law

now, but it wasn't then. There were other real issues we cared

about. For example, we sponsored an interracial swimming party

at our pool in Napa and received neighbors' (and even supposedly

close friends') raised eyebrows. As a matter of fact, after the

"400 ad" appeared in the local paper, my brother and his wife

had a cross burned on their lawn. It was a matter of mistaken

identity, and my brother's wife was very upset. They both knew

prejudice was wrong but they hadn't yet dealt with it

personally. They weren't then ready to stand up and be counted,

and so resented being tarred by my beliefs. I guess the reason

I'm telling about these incidents now is that although Janet

and I were 'good time Charlie party-giving social people', and

although we did some of it partially for our own political and

social aggrandizement, we did have some things we believed in.

We fed our spirits as well as our egos.

When we were still living on the ranch hillside, long

before recycling and refuse health standards, I had dug an open

garbage pit about 8 feet square and deep, about 50 feet uphill

from our back door. My labor was cheap and garbage service

didn't exist there then. At a New Year's Eve party one over-

indulged well-dressed guest from San Francisco fell in and

couldn't get out. Don Searle remembers him mumbling something

about 'the indignity of it all', as we helped him out.

After another New Year's Eve celebration we found a party

guest in the bathtub the next morning. The same morning, I was

going to make some toast and although I smelled gas I didn't

stop to put two and two together and I still leaned over and

lit the oven--and it blew up in my face. The explosion singed

my hair, burnt off my eyebrows, blistered my cheeks and nose,

and after about 30 seconds it started to hurt like hell.

Providence apparently dictated that Arnold should sleep in the

bathtub because he waked up and drove me to the hospital

emergency room while Janet stayed with the kids and called the

doctor telling him to meet me there.

The ranch was an exciting house to live in but when, at

certain times of the year, the north wind hit it, if it was

going 45 miles-per-hour on the outside it only slowed to 20

inside. In other words the house was loose, the upstairs was a

firetrap, and although there was central heating, it was just a

wood furnace. To stoke it you had to go outside, down the slope

through the "garden" (untended, going wild) and in under the

house. A more finished house was what we wanted and was really

where we were headed, though I'm sure if we could have bought

the ranch at the time we would have, and tried to make it more

finished. We really liked the place and wanted to fix it up but

would only have done this if we owned it. Unky, or Nathan F.

Coombs, had built the ranch house in 1922, the year I was born,

as a bachelor's retreat. In 1954 he wasn't using it and was

generous in letting us live there rent free, but his generosity

didn't overcome his sentimental attachment and he refused to

sell it, absolutely, at any price or under any conditions.

Unky, though basically a good-hearted fellow, had his

limitations. He was an old school Republican born and raised,

and felt that poor people, including Blacks and Mexicans, were

not qualified to run things. He used to call them "poor

devils". My father, I think, to a lesser degree believed the

same thing. But he did not speak disparagingly of other races

or put them down politically, whereas Unky, as officeholder and

politician, did.

Unky supported a tax system favoring land owners and high-

income taxpayers. He was not in favor of "equality". (He may

have suspected this was wrong, but he wasn't going to do

anything about it.)

In 1960, a month after my disastrous defeat in the State

Senate Democratic Primary, we moved into a new house which we'd

built on another hillside about a mile from the ranch--in fact,

you could see one house from the other, across a small valley.

Our new place was large and modern and was surrounded by over

a hundred acres of dairy pasture for black and white Holstein

milk cows. A couple years later, when an elderly Aunt of

Janet's died and left her 10,000 dollars, we built a swimming

pool.

The new house fit well into our political posture except

we didn't have room in the driveway for parking fifty or a

hundred cars--so we just opened up the fence and let our guests

park in the adjacent pasture. It gave them something to talk

about when their sportscar fenders were licked spic 'n span by

the cows.

One guest complained that a cow had stuck its head in the

front window and licked the leather seats (maybe looking for

salt). Occasionally, after a party I'd forget to close the

fence and we'd awaken to cows galore in the garden. I could

usually, maybe with one of the kids helping, herd them back

through the fence. One of Janet's fears was of waking up and

finding a cow or two in the swimming pool. Her vivid

imagination led to the question, "How do I get it out?"

Over the years we had lots of parties and we often enjoyed

them, although we didn't enjoy nursing drunks away from their

cars and keys out of their hands. We took them back inside and

fed them cup after cup of coffee hoping to sober them up so

they could drive. Maybe we should've just tried to put them to

bed but drunks don't always stay down. They're crazy

sometimes--sometimes they fight you. We dealt mostly with men

under these circumstances--you really hurt their manhood by

implying they can't drive. But if you can get them to go to

sleep your troubles are mostly over. Sometimes the best thing

would've been to take them for a run in the hills, but you'd

get tired of running in the hills, at night in the rain. On

occasion, I was one of them--not the crazy kind but the

overindulged definitely.

Janet was a great sport throughout these parties,

particularly because it was my career being promoted and my

rewards were greater than hers. People often think that those

who give this kind of big party do it solely for ulterior (i.e.

political or self-promotional) purposes. This isn't any more

true than that they give them solely for fun. Normally (and I

think in Janet's and my case) you do have some long term

objective in mind when you entertain a political crowd, but in

giving all these parties we were't just shooting for the

future. We were living--living the way a lot of our society

lived then: giving parties, showing off how graciously we could

entertain, engaging in smart conversation, trying in one way or

another to succeed; enjoying, regardless of the future,

successes of the moment. (One time, when I was retiring

President of the Napa Lion's Club, instead of the traditional

dinner given for the board of directors, Janet and I gave a gin

fizz breakfast, in preparation for which we stayed up 'til

midnight three nights in a row, making crepes to serve.)

Granted we were more interested in making our mark with a

political and quasi-intellectual set than the country club

crowd, we still were doing our thing for the now--just as much

as Babbit and his Boosters, or the Got-rocks at the Hillsboro

Golf Club. ("Babbit", in Sinclair Lewis's novel, was a chamber

of commerce type, a small town Booster, community-minded in a

dollars and cents way.)

Following the 1960 defeat I stayed active in politics,

serving two terms as Chairman of the Democratic Central

Committee, serving as President of the Mental Health

Association of Napa County, and also leading the County Histor-

ical Society. I got into these things I guess because I was

willing, respectable, eager, capable of hard work, and had a

job which gave me flexibility. I knew how to listen (even if I

did not exactly feel like it sometimes) and how to use humor,

and I was learning how to lead. The above were activities that

I had to continue to maintain my identity as a leader, although

they also helped with the law business. By this time I fully

recognized this 'ulterior' motive to my community involvement.

Even before I was a Democrat I was acquiring and advertising a

potential political personality--President of the Cancer

Society, Co-leader of a Great Books discussion group, eleven

years as a school trustee, President of the Lion's Club (as

mentioned)--these were some of my 'leadership roles'--finally,

in 1966, my big second chance loomed on the horizon, and I was

almost too chicken to take it. The California Supreme Court had

ordered a special reapportionment of both houses of the

legislature, setting in motion a game of political musical

chairs, which in turn resulted in a vacant Assembly seat in my

district. I had a clear shot at it. It wasn't mine for the

asking, but it was mine for the taking. Though my chances were

excellent*, I was still a little slow to get started moving.

There's a pschological term called "infant omnipotence"--the

child believes the earth swings around it and by crying,

laughing, and showing off, it does seem to completely control

the behavior and movements of the others in its orbit--the

mother, the father, the nurse. Some of this "infant

omnipotence" may continue on in the growing or grown-up

individual--and when I ran for office in 1960 it's possible I

didn't totally percieve that I could be defeated, turned

against, by the big world centered around me (despite high

school proof that failure was possible).

I certainly wasn't very aware of the pain it'd inflict on

me. But getting beaten again would be bad--and if you lose too

many times you don't get a chance again, you're a loser--that's

what I told my younger son Peter, when he ran for Student Body

President the third time. I said, "Maybe you shouldn't do this,

you've lost twice now. You could get the image of being a

loser," but he went ahead anyway, against some great big

football player. He was too far into it to turn around. Peter

was quite little (he grew a lot later)--so when they went out

on the stage to give their speeches (I didn't actually see

this) he carried a box with him, stood on it, and said "Hello,

I'm Peter Dunlap, vote for me. Remember, good things come in

_________________

*No incumbent to beat, for one thing.

small packages." He won. (So much for my cautious pessimism).

I stewed for several weeks before deciding to run.

Finally, on a weekend afternoon, the decision was made. Janet

and I had been sitting at our diningroom table talking about

what I should do, and, responding to a knock on the door, I was

greeted by a representative of my American Legion Post. I'd

been an inactive and generally uninterested member for several

years and my dues were delinquent. When he asked me to

reactivate my membership by paying my dues, I did so on the

spot. When I rejoined Janet, she said, "Now I know you're going

to run."

As I think back on it now, a lot of important things

(including feeding the family of course) took place at that

same table where Janet and I had been sitting. At least 100

campaign meetings took place there. I made thousands of

phonecalls seated at one end, leaning back in my chair with my

feet all or partly on the table. It was a comfortable feeling.

I was at home and I was boss, at least of the diningroom table.

In my memory, events from 12 legislative years cluster

around this egg-shaped table--key campaign meetings in every

election from 1966 onward, hours of homework involving the

legislative decision-making process--(bringing 4 days mail home

to catch up with on a Saturday or a Sunday--sitting making

telephone calls all over the district)--and now, finally, I am

again seated here writing part of this book (part of it is

'handwritten', part is transcriptions or tapes David and I

made), trying to evaluate and put things into perspective both

personally, because they happened to me, and professionally,

because I think they have some political meaning. And, of

course, there's just a 'story' to be told, regardless of rea-

sons and perspectives.

The 1966 campaign was a great success. I did what I had to

do to win. Though we were involved in a few gimmicky photo opps

like my being judge of a ladies' fashion show at the Mare

Island Naval Officer's Club, I was able to run my campaign

based on real issues. After making the initial decision to run

I spent almost two days straight on the telephone asking for

support, and, for the most part, getting it. It looked like I

had my home county sewed up in the primary, but an industrious

reporter friend of mine waked me just before seven one morning

to tell me that it looked like one of my neighbors, Harry

McPherson, a retired school superintendent, was running against

me. He was an older man whom I thought I could out-campaign,

but he had plenty of money and some prestige. His presence in

the race would've scared me. Because I knew him, I called him

up to check. He told me it was really nothing serious, he'd

just filed a "Notice of Intent" in case he decided later he

wanted to run. At this point his wife, who happened to be

Jessamyn West, the well-known novelist, got on the other line

and, knowing I was listening, said, "Harry, if you run I not

only intend to vote for John Dunlap, I will also work in his

campaign, and, finally, I'm going to give him some money."

In the 1966 campaign, raising money was the second

essential--usually it's the first. And it's always the hardest

and the least fun. Janet and I spent 6,000 dollars of our own

money on the June primary; the rest ($5,000) came from friends

and fundraisers. By general election time we had run out of

cash and we had to rely on further fundraisers plus a few

personal donations. I got a couple of unsolicited contributions

from lobbyists who I guess figured I was going to win. But I

didn't know how to ask for contributions of this sort.

In midsummer I got a call from San Francisco Assemblyman

John Burton, introducing himself and wondering if he could help.

He said he'd heard I'd won the Democratic primary. I said all

goes well except money and he said he'd see if he could do

something. I knew John by reputation only. His older brother

Phil (who was by then in Congress) I had met and talked with

him at California Democratic Council board meetings on several

occasions. A week later John called again saying he had

arranged a lunch in San Francisco to which I SHOULD come. His

invitation was spoken in tone of command. He didn't say

anything about money. But I assumed it might be involved. I

attended, and found it to be hosted by Frank Vicenza, lobbyist

for the Milk Producer's Council.

Vicenza paid for the lunch, and invited to it Willie

Brown, George Moscone, Joe Gonsalves, and possibly a couple of

East Bay democrats. Lunch was at a fancy restaurant and after

eating, under instructions from Joe Gonsalves, we took turns

leaving the diningroom separately, with Vicenza meeting us at

the door, giving each of us a check from the Milk Producer's

Council.

This was a successful event for me. Not only had I gotten

500 dollars, but also I'd had the opportunity of getting to

meet Burton, Brown, and Moscone, Big City Democrats. To them I

may have been potentially a "good liberal". John Burton was

cultivating friends for the future.

I had actually seen Willie Brown before, at a California

Democratic Council meeting two years back, and I'd thought

something to myself like, "Willie Brown--he's that black

hotshot from San Francisco--no need for me to bother to meet

him now." --just remain in awe at a distance.

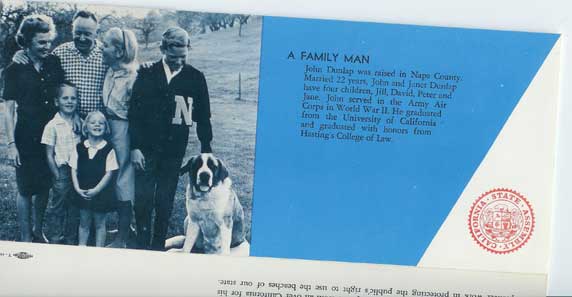

In 1966 neither I nor my campaign cohorts were really

experienced strategists. We did have good instincts. My

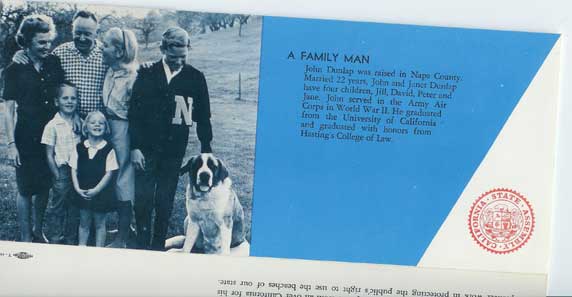

principal assets as a candidate were that I had been a

community leader and that I was part of a Good Traditional

American Family. (I don't know just what the 'Traditional

American Family' is--my idea of it would be pretty different

from that of many of the voters of my area.) I was a husband

and father. Also I was the son of a prune farmer, the grandson

of a county sheriff, and the nephew of a former State Senator.

I knew my family identification put me on the side of the good

guys, and everybody tends to buy a candidate done up in family

wrapping paper (though this is less true today than it was in

1966). My advisors knew it was worth a hell of a lot of votes

to have a good family picture and feature it in your campaign

literature.

The ranch had a high-up front porch with a

beautiful view (all the way up the valley to Mt. St. Helena).

It held fifty to a hundred guests and only creaked a little

under their weight. Yellow rose vines clung just over the porch

railing, and, a hundred yards off were all varieties of fruit

trees, untended but still thriving. The livingroom was also

big, warmed by wood floors walls, and ceilings, a protruding

fireplace with nooks on each side, and window seats under the

windows to the porch. With people crowded in and standing room

only a hundred people could listen to a speech.

Over a good many years Janet and I worked together

building my career. Sometimes we just gave large social parties

which I wouldn't have then admitted had any political

significance. Later many of our parties at the ranch were given

for specific partisan purposes, even large fundraisers like the

cocktail party for the late Congressman Clem Miller. The day

before that party we realized we didn't have enough furniture

and for 8 dollars bought a used couch which was a horrible red

and gold. For less than 2 dollars we purchased a can of black

fabric paint (Janet knew you could do this, I'd never heard of

it before)--it was called 'Fabspray' and it made the couch

really. . .well, not too bad. But we weren't sure how dry it'd

be for the party.

The next day I remember greeting guests on

the front porch and seeing a lady in a fancy hat and an elegant

white knitted dress, a gussied-up person who cared about how

she looked. If I'd had a chance to warn Janet to steer her away

from the couch I would have, but, as it turned out a little

later we both spotted her sitting there, and there was nothing

either of us could do--only when she got up about 20 minutes

later were we sure the paint was dry.

We were a good political couple. Janet could be more

gregarious than I. She was sincere and charming, I was just

sincere. But together we had a kind of crazy dedication and

willingness to try which made things work.

Being more sincere than charming, I had some political

convictions which I thought needed airing in staid old Napa. I

belonged to an ad hoc group which recognized that Napa was a

"lilywhite town". For instance, there were 300 blacks employed

at the Napa State Hospital located on the southern border of

the city, and none of them lived in Napa, all lived in Vallejo or

Fairfield. This was maybe 1963, about 100 years since the end of

the civil war.

Our group sponsored a public forum on the

subject. Afterward we got 400 people to include their names in

a full page ad in the Napa Register saying we as citizens would

rent or sell our homes to anyone who had the money to buy them

regardless of race, color, or creed. This is of course the law

now, but it wasn't then. There were other real issues we cared

about. For example, we sponsored an interracial swimming party

at our pool in Napa and received neighbors' (and even supposedly

close friends') raised eyebrows. As a matter of fact, after the

"400 ad" appeared in the local paper, my brother and his wife

had a cross burned on their lawn. It was a matter of mistaken

identity, and my brother's wife was very upset. They both knew

prejudice was wrong but they hadn't yet dealt with it

personally. They weren't then ready to stand up and be counted,

and so resented being tarred by my beliefs. I guess the reason

I'm telling about these incidents now is that although Janet

and I were 'good time Charlie party-giving social people', and

although we did some of it partially for our own political and

social aggrandizement, we did have some things we believed in.

We fed our spirits as well as our egos.

When we were still living on the ranch hillside, long

before recycling and refuse health standards, I had dug an open

garbage pit about 8 feet square and deep, about 50 feet uphill

from our back door. My labor was cheap and garbage service

didn't exist there then. At a New Year's Eve party one over-

indulged well-dressed guest from San Francisco fell in and

couldn't get out. Don Searle remembers him mumbling something

about 'the indignity of it all', as we helped him out.

After another New Year's Eve celebration we found a party

guest in the bathtub the next morning. The same morning, I was

going to make some toast and although I smelled gas I didn't

stop to put two and two together and I still leaned over and

lit the oven--and it blew up in my face. The explosion singed

my hair, burnt off my eyebrows, blistered my cheeks and nose,

and after about 30 seconds it started to hurt like hell.

Providence apparently dictated that Arnold should sleep in the

bathtub because he waked up and drove me to the hospital

emergency room while Janet stayed with the kids and called the

doctor telling him to meet me there.

The ranch was an exciting house to live in but when, at

certain times of the year, the north wind hit it, if it was

going 45 miles-per-hour on the outside it only slowed to 20

inside. In other words the house was loose, the upstairs was a

firetrap, and although there was central heating, it was just a

wood furnace. To stoke it you had to go outside, down the slope

through the "garden" (untended, going wild) and in under the

house. A more finished house was what we wanted and was really

where we were headed, though I'm sure if we could have bought

the ranch at the time we would have, and tried to make it more

finished. We really liked the place and wanted to fix it up but

would only have done this if we owned it. Unky, or Nathan F.

Coombs, had built the ranch house in 1922, the year I was born,

as a bachelor's retreat. In 1954 he wasn't using it and was

generous in letting us live there rent free, but his generosity

didn't overcome his sentimental attachment and he refused to

sell it, absolutely, at any price or under any conditions.

Unky, though basically a good-hearted fellow, had his

limitations. He was an old school Republican born and raised,

and felt that poor people, including Blacks and Mexicans, were

not qualified to run things. He used to call them "poor

devils". My father, I think, to a lesser degree believed the

same thing. But he did not speak disparagingly of other races

or put them down politically, whereas Unky, as officeholder and

politician, did.

Unky supported a tax system favoring land owners and high-

income taxpayers. He was not in favor of "equality". (He may

have suspected this was wrong, but he wasn't going to do

anything about it.)

In 1960, a month after my disastrous defeat in the State

Senate Democratic Primary, we moved into a new house which we'd

built on another hillside about a mile from the ranch--in fact,

you could see one house from the other, across a small valley.

Our new place was large and modern and was surrounded by over

a hundred acres of dairy pasture for black and white Holstein

milk cows. A couple years later, when an elderly Aunt of

Janet's died and left her 10,000 dollars, we built a swimming

pool.

The new house fit well into our political posture except

we didn't have room in the driveway for parking fifty or a

hundred cars--so we just opened up the fence and let our guests

park in the adjacent pasture. It gave them something to talk

about when their sportscar fenders were licked spic 'n span by

the cows.

One guest complained that a cow had stuck its head in the

front window and licked the leather seats (maybe looking for

salt). Occasionally, after a party I'd forget to close the

fence and we'd awaken to cows galore in the garden. I could

usually, maybe with one of the kids helping, herd them back

through the fence. One of Janet's fears was of waking up and

finding a cow or two in the swimming pool. Her vivid

imagination led to the question, "How do I get it out?"

Over the years we had lots of parties and we often enjoyed

them, although we didn't enjoy nursing drunks away from their

cars and keys out of their hands. We took them back inside and

fed them cup after cup of coffee hoping to sober them up so

they could drive. Maybe we should've just tried to put them to

bed but drunks don't always stay down. They're crazy

sometimes--sometimes they fight you. We dealt mostly with men

under these circumstances--you really hurt their manhood by

implying they can't drive. But if you can get them to go to

sleep your troubles are mostly over. Sometimes the best thing

would've been to take them for a run in the hills, but you'd

get tired of running in the hills, at night in the rain. On

occasion, I was one of them--not the crazy kind but the

overindulged definitely.

Janet was a great sport throughout these parties,

particularly because it was my career being promoted and my

rewards were greater than hers. People often think that those

who give this kind of big party do it solely for ulterior (i.e.

political or self-promotional) purposes. This isn't any more

true than that they give them solely for fun. Normally (and I

think in Janet's and my case) you do have some long term

objective in mind when you entertain a political crowd, but in

giving all these parties we were't just shooting for the

future. We were living--living the way a lot of our society

lived then: giving parties, showing off how graciously we could

entertain, engaging in smart conversation, trying in one way or

another to succeed; enjoying, regardless of the future,

successes of the moment. (One time, when I was retiring

President of the Napa Lion's Club, instead of the traditional

dinner given for the board of directors, Janet and I gave a gin

fizz breakfast, in preparation for which we stayed up 'til

midnight three nights in a row, making crepes to serve.)

Granted we were more interested in making our mark with a

political and quasi-intellectual set than the country club

crowd, we still were doing our thing for the now--just as much

as Babbit and his Boosters, or the Got-rocks at the Hillsboro

Golf Club. ("Babbit", in Sinclair Lewis's novel, was a chamber

of commerce type, a small town Booster, community-minded in a

dollars and cents way.)

Following the 1960 defeat I stayed active in politics,

serving two terms as Chairman of the Democratic Central

Committee, serving as President of the Mental Health

Association of Napa County, and also leading the County Histor-

ical Society. I got into these things I guess because I was

willing, respectable, eager, capable of hard work, and had a

job which gave me flexibility. I knew how to listen (even if I

did not exactly feel like it sometimes) and how to use humor,

and I was learning how to lead. The above were activities that

I had to continue to maintain my identity as a leader, although

they also helped with the law business. By this time I fully

recognized this 'ulterior' motive to my community involvement.

Even before I was a Democrat I was acquiring and advertising a

potential political personality--President of the Cancer

Society, Co-leader of a Great Books discussion group, eleven

years as a school trustee, President of the Lion's Club (as

mentioned)--these were some of my 'leadership roles'--finally,

in 1966, my big second chance loomed on the horizon, and I was

almost too chicken to take it. The California Supreme Court had

ordered a special reapportionment of both houses of the

legislature, setting in motion a game of political musical

chairs, which in turn resulted in a vacant Assembly seat in my

district. I had a clear shot at it. It wasn't mine for the

asking, but it was mine for the taking. Though my chances were

excellent*, I was still a little slow to get started moving.

There's a pschological term called "infant omnipotence"--the

child believes the earth swings around it and by crying,

laughing, and showing off, it does seem to completely control

the behavior and movements of the others in its orbit--the

mother, the father, the nurse. Some of this "infant

omnipotence" may continue on in the growing or grown-up

individual--and when I ran for office in 1960 it's possible I

didn't totally percieve that I could be defeated, turned

against, by the big world centered around me (despite high

school proof that failure was possible).

I certainly wasn't very aware of the pain it'd inflict on

me. But getting beaten again would be bad--and if you lose too

many times you don't get a chance again, you're a loser--that's

what I told my younger son Peter, when he ran for Student Body

President the third time. I said, "Maybe you shouldn't do this,

you've lost twice now. You could get the image of being a

loser," but he went ahead anyway, against some great big

football player. He was too far into it to turn around. Peter

was quite little (he grew a lot later)--so when they went out

on the stage to give their speeches (I didn't actually see

this) he carried a box with him, stood on it, and said "Hello,

I'm Peter Dunlap, vote for me. Remember, good things come in

_________________

*No incumbent to beat, for one thing.

small packages." He won. (So much for my cautious pessimism).

I stewed for several weeks before deciding to run.

Finally, on a weekend afternoon, the decision was made. Janet

and I had been sitting at our diningroom table talking about

what I should do, and, responding to a knock on the door, I was

greeted by a representative of my American Legion Post. I'd

been an inactive and generally uninterested member for several

years and my dues were delinquent. When he asked me to

reactivate my membership by paying my dues, I did so on the

spot. When I rejoined Janet, she said, "Now I know you're going

to run."

As I think back on it now, a lot of important things

(including feeding the family of course) took place at that

same table where Janet and I had been sitting. At least 100

campaign meetings took place there. I made thousands of

phonecalls seated at one end, leaning back in my chair with my

feet all or partly on the table. It was a comfortable feeling.

I was at home and I was boss, at least of the diningroom table.

In my memory, events from 12 legislative years cluster

around this egg-shaped table--key campaign meetings in every

election from 1966 onward, hours of homework involving the

legislative decision-making process--(bringing 4 days mail home

to catch up with on a Saturday or a Sunday--sitting making

telephone calls all over the district)--and now, finally, I am

again seated here writing part of this book (part of it is

'handwritten', part is transcriptions or tapes David and I

made), trying to evaluate and put things into perspective both

personally, because they happened to me, and professionally,

because I think they have some political meaning. And, of

course, there's just a 'story' to be told, regardless of rea-

sons and perspectives.

The 1966 campaign was a great success. I did what I had to

do to win. Though we were involved in a few gimmicky photo opps

like my being judge of a ladies' fashion show at the Mare

Island Naval Officer's Club, I was able to run my campaign

based on real issues. After making the initial decision to run

I spent almost two days straight on the telephone asking for

support, and, for the most part, getting it. It looked like I

had my home county sewed up in the primary, but an industrious

reporter friend of mine waked me just before seven one morning

to tell me that it looked like one of my neighbors, Harry

McPherson, a retired school superintendent, was running against

me. He was an older man whom I thought I could out-campaign,

but he had plenty of money and some prestige. His presence in

the race would've scared me. Because I knew him, I called him

up to check. He told me it was really nothing serious, he'd

just filed a "Notice of Intent" in case he decided later he

wanted to run. At this point his wife, who happened to be

Jessamyn West, the well-known novelist, got on the other line

and, knowing I was listening, said, "Harry, if you run I not

only intend to vote for John Dunlap, I will also work in his

campaign, and, finally, I'm going to give him some money."

In the 1966 campaign, raising money was the second

essential--usually it's the first. And it's always the hardest

and the least fun. Janet and I spent 6,000 dollars of our own

money on the June primary; the rest ($5,000) came from friends

and fundraisers. By general election time we had run out of

cash and we had to rely on further fundraisers plus a few

personal donations. I got a couple of unsolicited contributions

from lobbyists who I guess figured I was going to win. But I

didn't know how to ask for contributions of this sort.

In midsummer I got a call from San Francisco Assemblyman

John Burton, introducing himself and wondering if he could help.

He said he'd heard I'd won the Democratic primary. I said all

goes well except money and he said he'd see if he could do

something. I knew John by reputation only. His older brother

Phil (who was by then in Congress) I had met and talked with

him at California Democratic Council board meetings on several

occasions. A week later John called again saying he had

arranged a lunch in San Francisco to which I SHOULD come. His

invitation was spoken in tone of command. He didn't say

anything about money. But I assumed it might be involved. I

attended, and found it to be hosted by Frank Vicenza, lobbyist

for the Milk Producer's Council.

Vicenza paid for the lunch, and invited to it Willie

Brown, George Moscone, Joe Gonsalves, and possibly a couple of

East Bay democrats. Lunch was at a fancy restaurant and after

eating, under instructions from Joe Gonsalves, we took turns

leaving the diningroom separately, with Vicenza meeting us at

the door, giving each of us a check from the Milk Producer's

Council.

This was a successful event for me. Not only had I gotten

500 dollars, but also I'd had the opportunity of getting to

meet Burton, Brown, and Moscone, Big City Democrats. To them I

may have been potentially a "good liberal". John Burton was

cultivating friends for the future.

I had actually seen Willie Brown before, at a California

Democratic Council meeting two years back, and I'd thought

something to myself like, "Willie Brown--he's that black

hotshot from San Francisco--no need for me to bother to meet

him now." --just remain in awe at a distance.

In 1966 neither I nor my campaign cohorts were really

experienced strategists. We did have good instincts. My

principal assets as a candidate were that I had been a

community leader and that I was part of a Good Traditional

American Family. (I don't know just what the 'Traditional

American Family' is--my idea of it would be pretty different

from that of many of the voters of my area.) I was a husband

and father. Also I was the son of a prune farmer, the grandson

of a county sheriff, and the nephew of a former State Senator.

I knew my family identification put me on the side of the good

guys, and everybody tends to buy a candidate done up in family

wrapping paper (though this is less true today than it was in

1966). My advisors knew it was worth a hell of a lot of votes

to have a good family picture and feature it in your campaign

literature.

The family pictures were all loving and smiling; we

didn't have any of Janet and me trying to stop the kids from

throwing food at the diningroom table, or shouting at each

other in an unbecoming way. We put our best foot forward. We

were now a political family, with an extra reason to hide that

part of our private activities which was embarrasing. We cared

not only what our neighbors thought, but also what a quarter of

a million political neighbors thought.

The family pictures were all loving and smiling; we

didn't have any of Janet and me trying to stop the kids from

throwing food at the diningroom table, or shouting at each

other in an unbecoming way. We put our best foot forward. We

were now a political family, with an extra reason to hide that

part of our private activities which was embarrasing. We cared

not only what our neighbors thought, but also what a quarter of

a million political neighbors thought.

My campaign literature, aside from concentrating on the

Family, and my community service, talked about Selective Tax

Relief, Quality Education, and Conservation. I didn't emphasize

my more liberal philosophies. Except when somebody asked me, I

didn't mention that I was opposed to the death penalty, and I

didn't proclaim to the general public that I was not horrified

by the term 'socialist'. Of course I wasn't a 'socialist'--I've

never considered myself the proper subject of any 'ist' or

'ism'. But I certainly agreed with some socialist concepts.

Part of the job of our campaign meetings was to figure out

how to translate our philosophies into practical political

positions.

I remember these meetings with nostalgia. It was

usually the same nucleus of friends and allies, meeting to work

and drink coffee, moving on later to wine and talk. I don't

know if it was the wine or the thoughts we shared or both, but

a feeling of camaraderie, mutual acceptance, and trust

developed. I could tell my closest advisors about things

worrying me and have them not shame me for worrying. They

accepted me as I was and I took their advice to heart. We were

'young people out to make our mark on the world'. We were

serious, but no more than was necessary--sometimes we'd just

sit around and make cracks about my opponent, or about

ourselves. One friend, who thought me too liberal, suggested I

head the "Regressive Regurgitants' wing of the Democratic Party

(...Circular Thinking Cud Chewers?).

He spent several hours designing a campaign brochure calculated

to make the most serious of us smile. I appreciated it at the

time but I like it even more now. I sometimes had a little

trouble taking myself lightly.*

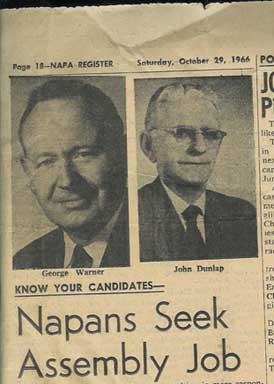

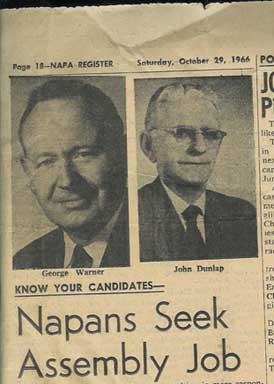

The Republicans had chosen as their figurehead the boss

of the downtown Chrysler-Plymouth dealership. At one time, he

had been Mayor of Napa. He was 70 years old and didn't look a

day younger. To our delight he put his picture on his

billboards. I had mine on mine, and this was good, but in one

edition of the Napa Register where they gave the candidates a

free opportunity for statements with accompanying mug shots,

they reversed our photographs, and that was not good. The paper

caught the error in the process and corrected it after about a

third of the edition had come out, and this was good.

________________

*See Appendix 1B for Jim Fitch's Mock Brochure.

There wasn't much mudslinging in the campaign. Privately,

the Republican leaders looked on me as ultra-liberal bordering

on pinko (while, privately, my friends and I thought what a

good undertaker my opponent could be and talked about how we

were gonna whip the old bastard's ass), but the worst thing my

opponent had to say about me publically was there were 'too

many lawyers in the Assembly'. One time, he did call me a

'card-carrying picket'. In those days, the words 'card-

carrying' were normally associated with membership in the

Communist Party. They knew damn well I wasn't a Communist but

they invented a phrase which suggested this without out and out

lying.

The night of the primary election the Dunlap dining room

table was laden with food and booze. We borrowed three

television sets, and had radios in every room. Somebody had

made a chart like a game scoreboard on which to post the

results. We'd invited about twenty campaign people to join us

and watch and listen as the returns came in.

Almost from the start, they were favorable, and the

trusted core of advisors grew to over 100 as wellwishers

dropped in to congratulate the candidate. Fortunately, many

brought more hooch and food; a few brought too much consumed

booze (in other words, they were drunk when they got there).

Some of them, two women and a man, decided to go for a swim in

our pool, without suits. I learned about it after it had

happened. As Janet said, "We weren't happy about it but we

weren't exactly tearing our hair either." I was just glad that

the local newspaper reporter (who'd come out to take my

picture) hadn't spotted them and written up our victory party

as 'Another Orgy at the Dunlaps' (to use Janet's words once

again). When we had another victory party for the general

election in November, it was too cold to swim, but a friend

made a sign anyway, and posted it by the pool, "DANGER--NO

SWIMMING. RAW SEWAGE."

In the primary election I'd gotten as many votes as both

my opponents put together. In the November election I was due

to win again by a wide margin and I did. However, we didn't

take anything for granted and I ran scared. I did everything I

was supposed to do.

When I had first started to campaign, I'd realized there

was a large black population in Vallejo (the largest city in

the district). I remember getting a warning from my very much

Establishment Solano county campaign chairman. He had said,

"Don't campaign in the Black areas...you may get a few votes

there, but waves will reverberate to the white area and you'll

become less welcome generally." I ignored this advice.

For a long time, at least sixteen years living in near

all-white Napa, I had realized that blacks living in Vallejo

were disadvantaged by de facto housing segregation and unequal

educational systems. Segregated housing resulted in partially

segregated education opportunities. Because I was sincere in

believing I could help, I felt justified in seeking support for

my campaign, in the Black and Phillipino communities. Local

members of the Vallejo NAACP and Phillipino community worked in

my campaign and I was proud to have their help and I don't

think it hurt me with many other voters.

Two weeks before the general election, I was going door to

door campaigning, handing out brochures, saying my name and

asking people for their vote, in a heavily Democratic district

in Vallejo. I noticed parked cars sporting both Dunlap and

Reagan bumper strips on the same car, and some of the houses

had similar pairs of opposites for lawn signs. I rang their

doorbells reluctantly. Reagan was now favored by the polls, as

was I. When I told Dave Evans, my campaign manager, about this

later, he said people were obviously not listening to me or

they wouldn't be supporting both Reagan and me--"Just keep your

necktie straight, your hair short, and a smile on your face.

Show them the picture of your family and keep your yap shut",

Dave told me, only partly in jest.

"Dunlap and Reagan"--this was a schizophrenic way to vote

but one which happens all the time--it merely illustrates that

often the public perception of political candidates is not

accurate, or at least not philosophically consistent. People

saw me as being more conservative than I was (possibly because

of my Republican family history), and Reagan was a good actor

and I'm sure appeared to be more compassionate than his

political philosophy.*

Reagan and I, though our signs stood united on common

lawns, were actually quite a 'Pair of Opposites'. "Pairs of

Opposites" is a pet phrase of mine, which I first picked up

from the Bhagavad Gita, in the God Krishna's advice to the

warrior Arjuna: (paraphrased from memory)

Be not blinded by pairs of opposites, the changeful

things of finite life. Life and Death are but pairs

of opposites, the changeful things of finite life.

But Dwelleth Thou within the greater aspect: Being--

Don't get caught up in goodguy badguy thinking--don't waste

your energy on it. You can waste a lot of time in political

_____________

*Which was, "There is too much government. People know better

how to spend the money than the government does. Private

initiative and capital can best solve most problems, except

that we need to have a strong military capacity." The end

result of this philosophy, of course, is domination of society

by the wealthy..."Those that have gits." The newly created

preponderant share of wealth goes to the more wealthy. 41

debate that merely points out a different aspect of the same

thing--in the minds of the people who voted for us in both in

the Dunlap/Reagan landslide of '66, we were united--but in my

mind we weren't just two more of the 'changeful things of

finite life', we were genuine opposites. Krishna's advice to

Arjuna involved a more catastrophic setting than mine at the

Capitol with Reagan. Arjuna had to decide whether or not to

take arms in a fratracidal battle. Actually killing his kin

would be wrong, but not to take part was to neglect his duty

and risk cowardice. How coming to terms with the Greater

Aspect: Being--helped him make his decision, I'm not sure, but

I guess it correlates to what we call "looking at the big

picture"--something I don't think Reagan had the will to do.

My battles with Reagan were not life and death but they were vital

in essence. He promoted the superficial viewpoint of a wealthy

Republican constituency, I believed that government had to be

more genuinely representative of all factions.

When Reagan had won his primary election in June 1966,

most organization Democrats rejoiced--we saw him as

representing only the radical fringe of the Republican party,

and we thought it'd be easier to beat a grade B movie actor

than George Christopher, former Mayor of San Francisco, a

seasoned, moderate professional. We didn't realize that a

large segment of the public was looking for something new. They

were impatient with politics as usual and that meant

'politicians'. Why not elect actors? We underestimated also

Reagan's skill as an actor and his ability to create the image

of being a reformer.

The night of the lawnsigns, Dave and I made light of the

situation and didn't really go into its serious implications,

but without saying it we knew then that Reagan was going to be

our next Governor.

I'm not sure what difference, if any, my election made to

Ronald Reagan, but I know his election made a big difference to

me . When I asked myself, at the Governor's Ball, 'Where do I

go from here?' I guess I should've known that my course was

partially charted for me just by Reagan's presence and power.

Instead of going to the Capitol to work with Governor Pat

Brown, a 60 year old knowledgeable and problem-solving

politician, for four more years of Democratic Progress, a large

part of my energy for the next 8 years would be taken up in

fighting the forces of reaction represented by Governor Reagan.

I did make a credible showing, carrying Yolo County by 400,

losing Napa by 4,000.

It hurt to lose, even if my friends did say 'the masses

are asses'--it was my own failure to convince them that I was

the wiser choice of candidates. I'd been a little greedy and I

knew it. It was a personal defeat for me and a defeat for

liberals in general, and I'd pretty clearly become the

candidate of innovation, speaking out against the death

penalty, criticizing tax loopholes for corporations, and taking

progressive stands on more obscure local issues. I wondered a

little if I hadn't been afraid of success and deliberately

bitten off more than I could chew. I could've run for that

Assembly seat and won. I don't regret losing now, but it sure

hurt then.

I did make a credible showing, carrying Yolo County by 400,

losing Napa by 4,000.

It hurt to lose, even if my friends did say 'the masses

are asses'--it was my own failure to convince them that I was

the wiser choice of candidates. I'd been a little greedy and I

knew it. It was a personal defeat for me and a defeat for

liberals in general, and I'd pretty clearly become the

candidate of innovation, speaking out against the death

penalty, criticizing tax loopholes for corporations, and taking

progressive stands on more obscure local issues. I wondered a

little if I hadn't been afraid of success and deliberately

bitten off more than I could chew. I could've run for that

Assembly seat and won. I don't regret losing now, but it sure

hurt then.

In 1958 we lived in a big, old, rustic but charming ranch

house perched among live oak trees on a valley hillside east of

Napa. It was owned by my uncle, who was incidentally my senior

law partner in "Coombs, Dunlap, and Dunlap", and a Republican

State Senator.

In 1958 we lived in a big, old, rustic but charming ranch

house perched among live oak trees on a valley hillside east of

Napa. It was owned by my uncle, who was incidentally my senior

law partner in "Coombs, Dunlap, and Dunlap", and a Republican

State Senator.

The ranch had a high-up front porch with a

beautiful view (all the way up the valley to Mt. St. Helena).

It held fifty to a hundred guests and only creaked a little

under their weight. Yellow rose vines clung just over the porch

railing, and, a hundred yards off were all varieties of fruit

trees, untended but still thriving. The livingroom was also

big, warmed by wood floors walls, and ceilings, a protruding

fireplace with nooks on each side, and window seats under the

windows to the porch. With people crowded in and standing room

only a hundred people could listen to a speech.

Over a good many years Janet and I worked together

building my career. Sometimes we just gave large social parties

which I wouldn't have then admitted had any political

significance. Later many of our parties at the ranch were given

for specific partisan purposes, even large fundraisers like the

cocktail party for the late Congressman Clem Miller. The day

before that party we realized we didn't have enough furniture

and for 8 dollars bought a used couch which was a horrible red

and gold. For less than 2 dollars we purchased a can of black

fabric paint (Janet knew you could do this, I'd never heard of

it before)--it was called 'Fabspray' and it made the couch

really. . .well, not too bad. But we weren't sure how dry it'd

be for the party.

The next day I remember greeting guests on

the front porch and seeing a lady in a fancy hat and an elegant

white knitted dress, a gussied-up person who cared about how

she looked. If I'd had a chance to warn Janet to steer her away

from the couch I would have, but, as it turned out a little

later we both spotted her sitting there, and there was nothing

either of us could do--only when she got up about 20 minutes

later were we sure the paint was dry.

We were a good political couple. Janet could be more

gregarious than I. She was sincere and charming, I was just

sincere. But together we had a kind of crazy dedication and

willingness to try which made things work.

Being more sincere than charming, I had some political

convictions which I thought needed airing in staid old Napa. I

belonged to an ad hoc group which recognized that Napa was a

"lilywhite town". For instance, there were 300 blacks employed

at the Napa State Hospital located on the southern border of

the city, and none of them lived in Napa, all lived in Vallejo or

Fairfield. This was maybe 1963, about 100 years since the end of

the civil war.

Our group sponsored a public forum on the

subject. Afterward we got 400 people to include their names in

a full page ad in the Napa Register saying we as citizens would

rent or sell our homes to anyone who had the money to buy them

regardless of race, color, or creed. This is of course the law

now, but it wasn't then. There were other real issues we cared

about. For example, we sponsored an interracial swimming party

at our pool in Napa and received neighbors' (and even supposedly

close friends') raised eyebrows. As a matter of fact, after the

"400 ad" appeared in the local paper, my brother and his wife

had a cross burned on their lawn. It was a matter of mistaken

identity, and my brother's wife was very upset. They both knew

prejudice was wrong but they hadn't yet dealt with it

personally. They weren't then ready to stand up and be counted,

and so resented being tarred by my beliefs. I guess the reason

I'm telling about these incidents now is that although Janet

and I were 'good time Charlie party-giving social people', and

although we did some of it partially for our own political and

social aggrandizement, we did have some things we believed in.

We fed our spirits as well as our egos.

When we were still living on the ranch hillside, long

before recycling and refuse health standards, I had dug an open

garbage pit about 8 feet square and deep, about 50 feet uphill

from our back door. My labor was cheap and garbage service

didn't exist there then. At a New Year's Eve party one over-

indulged well-dressed guest from San Francisco fell in and

couldn't get out. Don Searle remembers him mumbling something

about 'the indignity of it all', as we helped him out.

After another New Year's Eve celebration we found a party

guest in the bathtub the next morning. The same morning, I was

going to make some toast and although I smelled gas I didn't

stop to put two and two together and I still leaned over and

lit the oven--and it blew up in my face. The explosion singed

my hair, burnt off my eyebrows, blistered my cheeks and nose,

and after about 30 seconds it started to hurt like hell.

Providence apparently dictated that Arnold should sleep in the

bathtub because he waked up and drove me to the hospital

emergency room while Janet stayed with the kids and called the

doctor telling him to meet me there.

The ranch was an exciting house to live in but when, at

certain times of the year, the north wind hit it, if it was

going 45 miles-per-hour on the outside it only slowed to 20

inside. In other words the house was loose, the upstairs was a

firetrap, and although there was central heating, it was just a

wood furnace. To stoke it you had to go outside, down the slope

through the "garden" (untended, going wild) and in under the

house. A more finished house was what we wanted and was really

where we were headed, though I'm sure if we could have bought

the ranch at the time we would have, and tried to make it more

finished. We really liked the place and wanted to fix it up but

would only have done this if we owned it. Unky, or Nathan F.

Coombs, had built the ranch house in 1922, the year I was born,

as a bachelor's retreat. In 1954 he wasn't using it and was

generous in letting us live there rent free, but his generosity

didn't overcome his sentimental attachment and he refused to

sell it, absolutely, at any price or under any conditions.

Unky, though basically a good-hearted fellow, had his

limitations. He was an old school Republican born and raised,

and felt that poor people, including Blacks and Mexicans, were

not qualified to run things. He used to call them "poor

devils". My father, I think, to a lesser degree believed the

same thing. But he did not speak disparagingly of other races

or put them down politically, whereas Unky, as officeholder and

politician, did.

Unky supported a tax system favoring land owners and high-

income taxpayers. He was not in favor of "equality". (He may

have suspected this was wrong, but he wasn't going to do

anything about it.)

In 1960, a month after my disastrous defeat in the State

Senate Democratic Primary, we moved into a new house which we'd

built on another hillside about a mile from the ranch--in fact,

you could see one house from the other, across a small valley.

Our new place was large and modern and was surrounded by over

a hundred acres of dairy pasture for black and white Holstein

milk cows. A couple years later, when an elderly Aunt of

Janet's died and left her 10,000 dollars, we built a swimming

pool.

The new house fit well into our political posture except

we didn't have room in the driveway for parking fifty or a

hundred cars--so we just opened up the fence and let our guests

park in the adjacent pasture. It gave them something to talk

about when their sportscar fenders were licked spic 'n span by

the cows.

One guest complained that a cow had stuck its head in the

front window and licked the leather seats (maybe looking for

salt). Occasionally, after a party I'd forget to close the

fence and we'd awaken to cows galore in the garden. I could

usually, maybe with one of the kids helping, herd them back

through the fence. One of Janet's fears was of waking up and

finding a cow or two in the swimming pool. Her vivid

imagination led to the question, "How do I get it out?"

Over the years we had lots of parties and we often enjoyed

them, although we didn't enjoy nursing drunks away from their

cars and keys out of their hands. We took them back inside and

fed them cup after cup of coffee hoping to sober them up so

they could drive. Maybe we should've just tried to put them to

bed but drunks don't always stay down. They're crazy

sometimes--sometimes they fight you. We dealt mostly with men

under these circumstances--you really hurt their manhood by

implying they can't drive. But if you can get them to go to

sleep your troubles are mostly over. Sometimes the best thing

would've been to take them for a run in the hills, but you'd

get tired of running in the hills, at night in the rain. On

occasion, I was one of them--not the crazy kind but the

overindulged definitely.

Janet was a great sport throughout these parties,

particularly because it was my career being promoted and my

rewards were greater than hers. People often think that those

who give this kind of big party do it solely for ulterior (i.e.

political or self-promotional) purposes. This isn't any more

true than that they give them solely for fun. Normally (and I

think in Janet's and my case) you do have some long term

objective in mind when you entertain a political crowd, but in

giving all these parties we were't just shooting for the

future. We were living--living the way a lot of our society

lived then: giving parties, showing off how graciously we could

entertain, engaging in smart conversation, trying in one way or

another to succeed; enjoying, regardless of the future,

successes of the moment. (One time, when I was retiring

President of the Napa Lion's Club, instead of the traditional

dinner given for the board of directors, Janet and I gave a gin

fizz breakfast, in preparation for which we stayed up 'til

midnight three nights in a row, making crepes to serve.)

Granted we were more interested in making our mark with a

political and quasi-intellectual set than the country club

crowd, we still were doing our thing for the now--just as much

as Babbit and his Boosters, or the Got-rocks at the Hillsboro

Golf Club. ("Babbit", in Sinclair Lewis's novel, was a chamber

of commerce type, a small town Booster, community-minded in a

dollars and cents way.)

Following the 1960 defeat I stayed active in politics,

serving two terms as Chairman of the Democratic Central

Committee, serving as President of the Mental Health

Association of Napa County, and also leading the County Histor-

ical Society. I got into these things I guess because I was

willing, respectable, eager, capable of hard work, and had a

job which gave me flexibility. I knew how to listen (even if I

did not exactly feel like it sometimes) and how to use humor,

and I was learning how to lead. The above were activities that

I had to continue to maintain my identity as a leader, although

they also helped with the law business. By this time I fully

recognized this 'ulterior' motive to my community involvement.

Even before I was a Democrat I was acquiring and advertising a

potential political personality--President of the Cancer

Society, Co-leader of a Great Books discussion group, eleven

years as a school trustee, President of the Lion's Club (as