Chapter Five

Conference at the Capitol Tamale Cafe

At noon, the same day as I'd passed the Mountain Lion

Bill, Alan and I walked across the Capitol Park to our lunch

meeting with a UCLA law professor who had flown up to testify

for our tax bill at the 3 p.m. hearing. We shared the walk

with half the working population of the Capitol; a thousand

or so people, but the grounds absorbed us all easily. The

Capitol building itself, like most State Capitols, is modeled

after the gold-domed building in Washington D.C. It's a blend

of 19th Century grandeur and 50's granite-faced additions.

The grays of the granite go well with the greens of the park

and you can get lost inside the labrinth of the Capitol's

cool tall halls just as you can lose yourself in the hundreds

of trees and succession of lawns in the park.

My son David wrote a Father's Day song for me in 1970,

the opening verse of which refers to the dome--

He was born on a prune ranch

and he dug his way to a Sacramento home

when he's not laying stone

for the barbecue pit

he's up reconstructing the Capitol Dome

Remembering the beauty of the Capitol Park brings a

feeling of peace, but also stirs up some longing. If I let

it, the longing could grow out of all proportion, 'welling up

from the depths of my soul'. I could work myself into a

lather over wanting to be back there, but I'd just be

fighting time. Then, in march 1970, I was 47; now I'm 80--I'd

still like to think 'the most important part of my life' is

ahead of me, but in a certain sense, it probably isn't. As

far as my opportunity to change the world is concerned, I've

probably had it. But then, "my son the writer" reminds me as

I say this, of the potential power of my book. "The Pen is

More Powerful Than the Treadmill"??

Still, I am a little jealous of the person I was then.

(I guess that's a standard reaction to aging). I don't think

I'd mind living that part of my life over again...this IS an

option in fantasy literature, at least. I'd have a chance to

hit the issues again--harder, with the confidence potential

I'd then only partially reached. And I'd cherish my friends a

little more along the way, and be the great father and

husband I wasn't. In short, what I long for is to surmount

(which means climb to the top of) the great wall of

expectation which I created for myself, and become the

perfect person I now imagine I might have been...if granted

the power to go back in time, I'm sure I'd also be given the

super powers I'd need for my mission...

Actually, I don't waste much time longing for lost

opportunities. It comes in (decreasing) phases.

I suppose if I wanted to go back to Sacramento badly

enough I might get the Assembly Sergeant-at-Arms to hire me

as a docent (docents are persons who conduct tours of

museums, opera houses, and other places of public interest).

I think I'd be better used conducting tours of the Capitol

grounds than running the elevator or serving coffee to the

Powers.

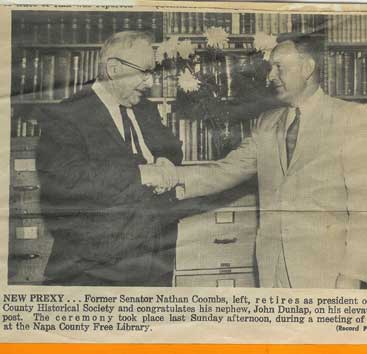

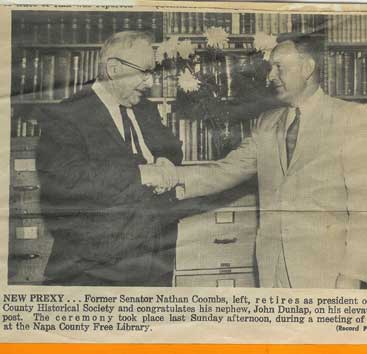

"Ladies and gentlemen, in this park there are 2900

botanical species, mostly native Californian, but there are

specimens from all over the world. There, is the Junipero

Serra Fountain, and There, is a plot of rare and unusual

hybrid camelias, and over here's the bench my uncle the

elderly Senator Coombs used to rest on when he fed the

squirrels. He was 80 when he retired from the legislature.

Still, I am a little jealous of the person I was then.

(I guess that's a standard reaction to aging). I don't think

I'd mind living that part of my life over again...this IS an

option in fantasy literature, at least. I'd have a chance to

hit the issues again--harder, with the confidence potential

I'd then only partially reached. And I'd cherish my friends a

little more along the way, and be the great father and

husband I wasn't. In short, what I long for is to surmount

(which means climb to the top of) the great wall of

expectation which I created for myself, and become the

perfect person I now imagine I might have been...if granted

the power to go back in time, I'm sure I'd also be given the

super powers I'd need for my mission...

Actually, I don't waste much time longing for lost

opportunities. It comes in (decreasing) phases.

I suppose if I wanted to go back to Sacramento badly

enough I might get the Assembly Sergeant-at-Arms to hire me

as a docent (docents are persons who conduct tours of

museums, opera houses, and other places of public interest).

I think I'd be better used conducting tours of the Capitol

grounds than running the elevator or serving coffee to the

Powers.

"Ladies and gentlemen, in this park there are 2900

botanical species, mostly native Californian, but there are

specimens from all over the world. There, is the Junipero

Serra Fountain, and There, is a plot of rare and unusual

hybrid camelias, and over here's the bench my uncle the

elderly Senator Coombs used to rest on when he fed the

squirrels. He was 80 when he retired from the legislature.

"These many long and crisscrossing sidewalks were where

my youngest daughter Jane and her friend Erin used to skate

when they came for a day's adventure at the Capitol. And,

here's another bench: it's where Assemblyman Willie Brown,

later Speaker and now Mayor of San Francisco, used to study bill

briefings during noon recess of Ways and Means Comittee

meetings (which he then chaired). I assume that in the rain

and the snow he sat somewhere else--in a private corner of

his office where he could shut himself off for periods of

time, say. I know personally how effective Willie could be as

Chairman of Ways and Means--I remember he would occasionally

cut an author's bill presentation short and explain it to us

better, and more quickly than was being done. At every

committee meeting he conducted he had read all the briefs on

all the bills, knew the arguments for and against; sometimes

I'm sure he knew the bills better than the authors

themselves. I'd known him for 16 years when he was Speaker

and knew he was smart as a whip but many other people didn't

know him this well. Because Willie indulges in what one might

call 'street talk', and because some people equate

intelligence with use of the 'King's English', a few have

underestimated Willie Brown's ability.

Continuing the 'docent' bit:

"This grass-covered area with the single bench is where

I sat in the center of a large circle of students having a

pow-wow when they marched on the Capitol in 1969, protesting

the Vietnam war.

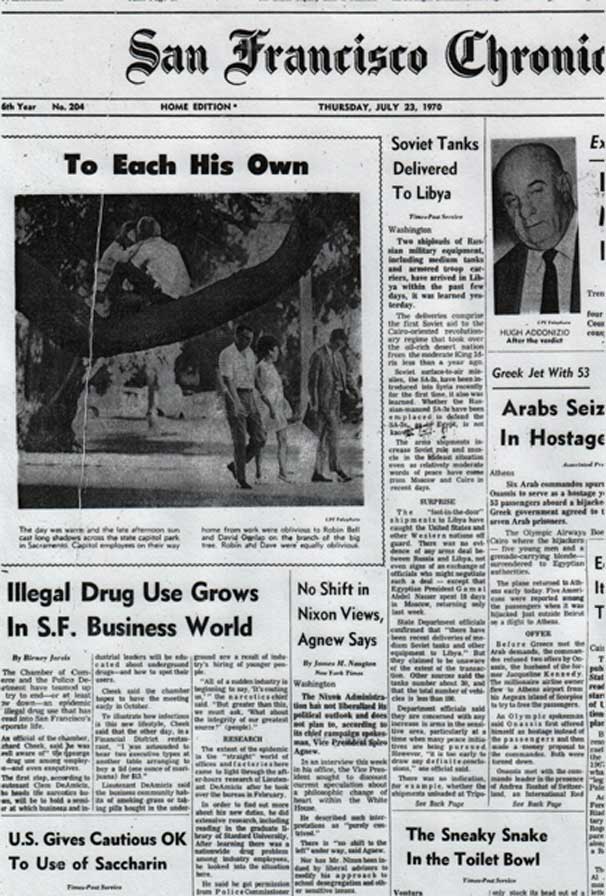

"And here, is Tulupis Grandeflora, or the Big Tulip Tree

I used to look at out of the window of my diminutive second

story "office-with-a-view" in 1967. And here--this good-sized

oak with spreading branches--is a very special tree. In this

tree my son David and his girl Robyn happened to have their

picture taken when they were up on a limb kissing on a hot

summer afternoon. David had visited with me that day and on

the way home he told me that he and Robyn had climbed a tree

and someone carrying a camera had come over, seeming amused,

and asked in a friendly way for their names. He didn't tell

me about the kissing or the photograph. I learned of that*

the next morning when Janet called me on the phone to tell me

David and Robyn's picture was on the front page of the Bay

Area's most prestigous newspaper, The San Francisco

Chronicle.

"These many long and crisscrossing sidewalks were where

my youngest daughter Jane and her friend Erin used to skate

when they came for a day's adventure at the Capitol. And,

here's another bench: it's where Assemblyman Willie Brown,

later Speaker and now Mayor of San Francisco, used to study bill

briefings during noon recess of Ways and Means Comittee

meetings (which he then chaired). I assume that in the rain

and the snow he sat somewhere else--in a private corner of

his office where he could shut himself off for periods of

time, say. I know personally how effective Willie could be as

Chairman of Ways and Means--I remember he would occasionally

cut an author's bill presentation short and explain it to us

better, and more quickly than was being done. At every

committee meeting he conducted he had read all the briefs on

all the bills, knew the arguments for and against; sometimes

I'm sure he knew the bills better than the authors

themselves. I'd known him for 16 years when he was Speaker

and knew he was smart as a whip but many other people didn't

know him this well. Because Willie indulges in what one might

call 'street talk', and because some people equate

intelligence with use of the 'King's English', a few have

underestimated Willie Brown's ability.

Continuing the 'docent' bit:

"This grass-covered area with the single bench is where

I sat in the center of a large circle of students having a

pow-wow when they marched on the Capitol in 1969, protesting

the Vietnam war.

"And here, is Tulupis Grandeflora, or the Big Tulip Tree

I used to look at out of the window of my diminutive second

story "office-with-a-view" in 1967. And here--this good-sized

oak with spreading branches--is a very special tree. In this

tree my son David and his girl Robyn happened to have their

picture taken when they were up on a limb kissing on a hot

summer afternoon. David had visited with me that day and on

the way home he told me that he and Robyn had climbed a tree

and someone carrying a camera had come over, seeming amused,

and asked in a friendly way for their names. He didn't tell

me about the kissing or the photograph. I learned of that*

the next morning when Janet called me on the phone to tell me

David and Robyn's picture was on the front page of the Bay

Area's most prestigous newspaper, The San Francisco

Chronicle.

________________

*As did we all.

The Chronicle might occasionally mention my activities

in a minor way buried in the center of the paper. I'd been

working my ass off for umpteen years and never came near page

one, while David and Robyn hit the jackpot by doing just what

comes naturally. Despite this goddamn irony I didn't feel

jealous. I was a little uptight, because as a controversial

legislator I preferred to appear personally traditional,

maybe even a little dull. Consequently, when family members

failed to follow the script, it made playing the lead a

little harder. Suppose I'd been defeated in the next

election--we'd never know if that was why. David and Robyn's

fame, it turned out, did no harm--just went down in family

history.

The chorus to David's father's day song goes:

I think he'll follow

in my footsteps (oh yeah)

when I'm leading up the treetrail

to the Future

I.E. I might make it to the front page of the Chronicle

sometime--or, a more general interpretation: that children,

if they lead full lifespans, always lead the way into the

future and are 'followed' in spirit by their parents.

Alan and I had pioneered tax reform ever since we hit

the Capitol in 1967. Our ideas were far more earthshaking

than the traditional pablum served by Reagan, or for that

matter than Jess Unruh's when he was Speaker. This year, we'd

spent hours working on the details in our offices, and The

Capitol Tamale Cafe, where we were headed for today's lunch

meeting, had long since become one of our conference rooms.

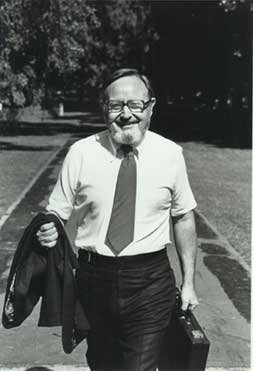

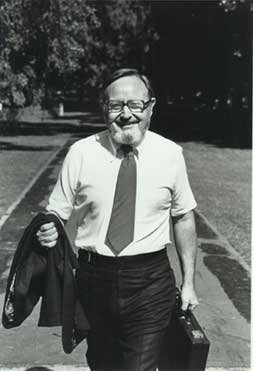

Back in 1967, Alan was 35, ten years younger than I.

I had the same crewcut I'd had in lawschool, and wore

relatively cheap storebought suits. My shirts were usually

white, my ties conservative, though sometimes I had a pretty

one. My favorite was sort of wooly-orange with white lines

running through it. People would look at it, and admire it,

and occasionally notice the small cloth label on it which

said 'Fabric Content Unknown'.

In 1967 Alan wore well-tailored expensive suits, the

ultimate in conservative good taste. His shirts were always

white. Anyone knowing us in 1967 might've said, "One comes

from a cow county and the other from Beverly Hills, but they

both look like the earnest young man applying for his first

job."

The chorus to David's father's day song goes:

I think he'll follow

in my footsteps (oh yeah)

when I'm leading up the treetrail

to the Future

I.E. I might make it to the front page of the Chronicle

sometime--or, a more general interpretation: that children,

if they lead full lifespans, always lead the way into the

future and are 'followed' in spirit by their parents.

Alan and I had pioneered tax reform ever since we hit

the Capitol in 1967. Our ideas were far more earthshaking

than the traditional pablum served by Reagan, or for that

matter than Jess Unruh's when he was Speaker. This year, we'd

spent hours working on the details in our offices, and The

Capitol Tamale Cafe, where we were headed for today's lunch

meeting, had long since become one of our conference rooms.

Back in 1967, Alan was 35, ten years younger than I.

I had the same crewcut I'd had in lawschool, and wore

relatively cheap storebought suits. My shirts were usually

white, my ties conservative, though sometimes I had a pretty

one. My favorite was sort of wooly-orange with white lines

running through it. People would look at it, and admire it,

and occasionally notice the small cloth label on it which

said 'Fabric Content Unknown'.

In 1967 Alan wore well-tailored expensive suits, the

ultimate in conservative good taste. His shirts were always

white. Anyone knowing us in 1967 might've said, "One comes

from a cow county and the other from Beverly Hills, but they

both look like the earnest young man applying for his first

job."

And in 1969, only a couple years later, here I was

'sporting long sideburns', no longer wearing a butch--and,

due to grow a beard in a couple more terms. At the time I

went to the Senate, Alan had started having his hair styled

and 'livened up'--actually, it looked good, once I got used

to it. In 1974, Alan joined me in the Senate, and by this

time we'd both gone whole hog and out of forty senators were

the only two with beards.

And in 1969, only a couple years later, here I was

'sporting long sideburns', no longer wearing a butch--and,

due to grow a beard in a couple more terms. At the time I

went to the Senate, Alan had started having his hair styled

and 'livened up'--actually, it looked good, once I got used

to it. In 1974, Alan joined me in the Senate, and by this

time we'd both gone whole hog and out of forty senators were

the only two with beards.

In the early 60's, at board meetings of the California

Democratic Council, Alan and I debated matters of policy as

seriously as if we'd been on the Supreme Court and had actual

power. In reality we were just two steps above Don Searle's

and my conversations at home in the early 50's. Now, in the

legislature, we may have still looked like beginners, but

even in '67 we knew the assembly wasn't just another board

meeting, and we had some knowledge of practical politics.

Legislators usually work alone, like hunters--80 hunters

in 80 offices. A bill belongs to its author just like a dog

belongs to one hunter--trained to point, flush and fetch at

one hunter's command-so, a bill is introduced, amended, and

set for hearing at the direction of its author. Co-authors

are usually just along for the ride with no power or

authority, but Alan and I piloted jointly.

Sharing ideals and sharing method are necessary to

cooperation between legislators. In January of '67 we shared

both and knew we'd be working together in Sacramento. We

didn't know our cooperation would become so close that the

words 'Dunlap/Sieroty' would be synonymous with quixotic tax

reform and the words 'Sieroty/Dunlap' would become a label

for Coastal Conservation. We were about to become a unique

pair--a true legislative partnership. I shared ideals with at

least ten other legislators and method with at least half of

them, but we didn't become legislative partners. The

difference lay in the fact that Alan and I were able to avoid

the almost inevitable ego conflict which made continuous

close cooperation between legislators impossible. Jess Unruh

said, "Politics is the art of taking credit."

It feels great to know that your name has been on the

front page of every major California newspaper in relation to

something you're proud of having done. You get the respect of

your fellow legislators, and you get publicity--you keep up

your public image as a winner, and this helps you get re-

elected. But the greatest value of publicity is 'for its own

sake'--it's like getting slapped on the back by your father

who says, "well done, son"--it's like a dozen curtain calls--

it's the greatest reward, the payoff. There's an awful ten-

dency to try to grab it all for yourself--to take whatever

you can get and not give any away by sharing credit with

other deserving legislators/people. There's also an awful

tendency to forget that publicity (the "art of taking

credit") is a sidetrack and not the main line. Doing things

which you can take genuine pride in ought to be foremost.

Alan's district was strongly Democratic and liberal, so

he didn't need publicity for job security. I didn't have it

so good; my district was blue collar lunch bucket Democratic

and not so liberal--some of my far out legislative activities

were best accomplished without publicity. I still personally

liked the limelight, and usually risked it. But along with

Alan I believed it was more important to try to get something

done than to bob and weave for credit and election. Alan's

part in this can't be minimized. He was generous both

dollarwise and personally. When we introduced our first

Coastal Conservation Bill we held press conferences over a

two day period in San Diego, L.A., Santa Barbara, San

Francisco, and Santa Rosa. Alan paid for most of our plane

transportation and hotel rooms out of his own pocket, and

when we made appearances in Northern California, my

bailiwick, he even pretended his sore throat was worse than

it was, so I'd have to do most of the talking and get most of

the press. Real generosity.

Alan was an idealist. Cynical colleagues would say,

"Sieroty's so idealistic he doesn't know when to come in out

of the rain." This is common language used by people who are

trying to put down someone better than they are. Contrary to

the criticism of his colleagues, Alan did know what the real

world was like, but he was willing to appear as an

uncompromising idealist if he thought it would enhance

change. Sometimes things happened because he wouldn't

compromise; sometimes his failure to compromise resulted in

inaction--nothing--zero. But nothing is sometimes better than

a bad bargain. You can always try again.

Alan was almost too good for the legislature, which had

its share of Machievellian opportunists and prima donnas.

Alan wasn't hunting for money--because he had it. He grew up

in a beautiful Beverly Hills mansion, with his family's real

estate interests scattered throughout the L.A. basin. Alan

didn't have to be centered under the Kleig lights all the

time--he wasn't a prima donna. I met his parents a couple of

times; their pride in Alan was genuine and obvious. I'm sure

they gave him personal as well as financial security; he

seemed as little interested in glory as he was in gold.

I don't mean to paint him as a saint; he had creature

wants and comforts like the rest of us. Though tall (he had

at least four inches on my 5' 9") he was a little heavy but

not fat. He had a sort of smooth full face and his hair was

rigidly combed when we first got to the Capitol. Alan almost

always had dessert when we ate out, rarely turning down the

cream puffs, choclate strawberry shortcake, cheesecake

mousse, or whatever else delicious was on the pastry cart at

the Tamale Cafe. By the time it rolled around I'd already had

my extra calories in a drink before lunch, or a couple

glasses of red wine with it.

During my 12 years at the Capitol my own

weight went up and down a lot, so I'm not really the

one to talk. If you've seen pictures of me you know I bounced

back and forth between being somewhat on the heavy side and

being just about right.( My weight was between 165 and 195,

depending on how hard I was working at holding it down.)*

With us at lunch that afternoon was the UCLA Tax Law

professor who Alan hoped would help us out as a witness on

our tax bill. As we sat down, the professor said, "I finally

read the details of your reform bill on the plane this

morning--I'm a law professor, not an economist, but I can

tell your bill would upset the Powers-That-Be in the business

world. It's got some good ideas but you don't really have a

chance, do you? You know more about your colleagues than I

do, but I sure know the Chamber of Commerce and Rotary club

bunch would be after your skins if your bill passes. Even in

Beverly Hills, Alan."

________________

*Since 1976 I don't have calories coming from alcohol and I

now get plenty of exercise. My weight hovers between 158 and

165, only slightly above what it was in 1943 when I went into

active duty in the Army Air Corps.

Sieroty responded, apologizing for not making it more

clear earlier, and definitely assuring the prof that we knew

our bill wasn't going to even get out of its first committee

let alone be passed by both houses and signed by Governor

Reagan. "But," Alan continued, "the bill is right in

principle and its policies need to be talked about seriously.

Most of our ideas aren't brand new but they haven't been

openly discussed and supported enough to catch fire with the

public." The professor said that he agreed with us in

principle, but that he wasn't sure it was wise to upset so

many applecarts all at once. I said, "All we need from you is

a few words attesting to the bill as a good lawyerlike job of

draftsmanship, that it's enforceable and legally calculated

to do what we say it does. You see, although we don't ask you

to literally endorse our economics, we'd like to use your

professional prestige to legitimate our innovation."

"It wouldn't be the first time I'd been used for a just

cause. I wanted to make sure it was just and was important.

Maybe you can tell me something about your general theory of

taxation?"

"Maybe I should tell you my 'Theory of Government'

first."

"All right."

I spoke to the Professor approximately as follows:

"To start things off, I could say something like:

government presents a way of distilling the best of humanity,

and institutionalizing it. Government also has to curb the

worst behavior--and not just classically recognized criminal

acts. Excesses of Capitalism have to be controlled too. The

representatives of Capitalism--Rotarians, Chamber of Commerce

people, others--have the money, and own the land and capital

goods. They pay the hucksters and the media to manipulate

public opinion. They call the shots, they have the

power...and if it weren't for government, Capitalists would

have all the power. There are degrees of membership in the

'Club of Capitalism', of course. And the adherents to the

Creed vary in their rabid application of it. Some may

consider Living ...Earning. Any points/dollars won in this

game must NOT be forfeit. 'Share only when you have

Everything'? One can forget ((or not learn)) other pleasures

and values while stockpiling up money. The more subtle values

aren't necessarily inate. Most people put off changing 'who

they are' until it's too late to significantly.

"As we've all been telling ourselves, there are a heck

of a lot more working men and women than there are wealthy

Capitalists, and the Constitution has given each one a vote.

And if working people voted as a unit, government would speak

for them. People who don't vote screw themselves--they

believe that government does't work or is Against Them--and

by not voting they make damn sure it's against them.

Statistics will indicate that 70 percent of those with an

annual income of $30,000 or more register and vote. For those

with an annual income of $10,000 or under, the figure is 25

percent voting. 'The Masses', of course, are in this second

second group, and have the power potential to control the

United States. This is why Reagan and other Republicans so

often say 'that government governs best, which governs

least'. The Republican party is the political standard bearer

for the forces of Capitalism and doesn't want the working

people, through government, labor unions, and consumer

organizations--through numbers--to exercise their power."

I might've continued my speech to the professor,

"Government can have a restrictive power, saying No-No to bad

capitalists when they exploit people and waste natural

resources, and can also have positive or creative powers--

creating Health, Education, and Welfare programs, for

example...creating food programs to prevent malnutrition and

mental and physical retardation in underpriviledged children,

and decent education programs to give them a chance to earn a

good living and lead productive lives. Programs such as these

benefit ordinary people more than the wealthy, who can buy

their own, if government isn't there.

"But, these things do cost a lot of money--so, my first

principle regarding taxes is that they be sufficient to raise

enough money. And in a highly populated, highly developed

country like the U.S., tax capital is an immense resource.

My second 'principle of taxation' is that we should get

a lot of the money from those who can afford to pay, the

wealthy. Though they earn more by far, their effort is not

necessarily greater than that of the teenager holding down

two jobs to buy a car, one at Burger King and one at Taco

Bell (and it could be less).

{invent chart or illustration demonstrating proper taxing of citizenry}

"The wealthy may argue that they should be taxed in the

same proportion as the poor or poorer but (as I say in more

detail later in this book) they benefit more from a number

of public services...and can give a reasonable amount to

government and still have plenty left for their luxuries.

"Admittedly, this is a way of using government in a

direction which tends to equalize wealth. However, it's

oversimplifying to say that all we want to do is soak the

rich; there's no need to punish the wealthy for their good

luck or their persistent enterprising. It's clear to me that

well-run Health, Education, and Welfare, are programs which

in the long run will benefit all society. All we need to do

is raise enough money so that government can do the job. We

aren't talking about handing out ice cream cones, or taking

tax dollars from the rich and casting them willy nilly into

the slums for people to pick up in their tin pails.

I noticed Mike Gage apparently leaving the restaurant

and called him over to the table. "Mike, this is Professor

Ernest Lernwell from UCLA--he's here to back us up on the tax

bill this afternoon."

"Did he bring his shovel to help you bury it?"

"Enough of your cynicism. As a matter of fact, I was

just gonna tell Alan and the Professor that I saw Unruh in

the can a little before adjournment--he said he was gonna

pick us up a couple of votes."

"Glad to have his help," Alan said.

Gage remained cynical and practical, "I'll bet. Count

'em when you get 'em."

"Have you had lunch, Mike?" Alan asked.

"Is that an offer?"

"Sure, join us."

"Actually, I brown-bagged it in the office before I came

over here--but I guess I could sit and watch you guys eat."

"You can watch," I said, "but don't touch."

"I'll sit between Alan and the professor--you're mean."

"That's the way it goes, Mike--the privileged class gets

the prize plates." Mike did not bother to challenge this.

"I've never liked how money separates people," the

professor said--"where they live, what they wear, what and

where they eat."

"We were just talking, Mike, about how Alan's and my

bill takes a step in the direction of equalizing things."

"And so is this the first step in your program? Taking

me to non-lunch?"

"You have to start somewhere."

"In Phase Two--I suppose the busboy and maitre d will

join us?"

"Like Martin Luther King..I have a dream," I said, "of

everybody eating at one big round table. And in a

philosophical sense, that's already the way it is. We're all

sitting together on the same big round world, all 'in the

same boat'--we just don't see we're sitting at the same

table."

"Bullshit," Mike said. "I can see we're sitting at the

same table."

"But don't be too sure you're gonna get the same food,

Mike."

"I didn't order anything."

"We have ordered or been ordered for--and according to

the order of things, you, Mike, will have one moldy biscuit

to eat; but that's not so bad, the professor doesn't have

anything at all. Nothing. I have a bowl of tomato-rice soup,

and an avocado sandwich with sprouts. And Alan, god bless

him, has steak and lobster; beautifully prepared potatoes au

gratin, asparagus with bernaise sauce, and a pot of the best

English tea. For dessert he will have demitasse, and a

meringue with ice cream and whipped cream."

"I don't believe it was entirely coincidental that you

picked me for that role, John."

"Okay, Alan, consider yourself well cast."

"All right, I'll accept my role. Get on with the action,

Mr. Playwright."

"The only further fact that we need to introduce is that

the four of us are all blind--four blind men sitting at a big

round table, each with only a vague sense of others being

present. We can smell something good coming from Alan's side

of the table--we can hear eating noises--but if we're blind,

nothing happens, except we eat. Mike eats his biscuit. I eat

all of my soup and sandwich. Alan with the bountiful repast

may eat it all or leave a little here or there. (Actually, in

keeping with his class, he would possibly only eat half.)

The professor, with nothing to eat, won't eat anything--I

don't know what he'll do--he may leave.

"And if we aren't blind--or if the blindfolds are

removed--my guess is that there'll be some sharing. I think

that Alan, if he's confronted, across the table--immediatly,

personally, with our plight, professor--would do something

about it. He wouldn't wait for the pickings from his plate

to be rooted from the garbage can later; he might more

energetically back programs to divide the meat

and potatoes in the kitchen. But you've got to remove the

blinders for this to happen. And the first situation--four

blind men--is more true to life--the rich and the poor, at

distant tables, do not percieve each other in any detail or,

usually, in any penetrating way.

"If Alan, as the lucky man at our round table, had

happened to order a light meal for dietietic purposes, he

wouldn't have had food to share, but he might've made a gift

of his jeweled watch or diamond tiepin, knowing it could be

converted to food--a lot of food."

Alan's and my tax program was a push, to try to do what

rich people might well do on their own if they really

understood the other guy's plight. I think they'd be willing

to settle for a BMW instead of a Rolls Royce and let the

difference in price go to worthwhile government programs.

This is putting government in the role of moral

overseer, of course--but it was never anything less than that

(a stoplight is a 'moral overseer' with an obvious

practical/protective function).

The 'four hungry men at a table' parable actually

occurred to me in 1984, sitting in a diningroom in Mendocino.

I was recently retired and working on this book. I lied about

the time and place, adding some lines to our dialogue

at the Capitol Tamale Cafe----but it is the kind of conversation

that could have happened at our lunch meeting thirteen years

earlier, particularly with Mike Gage or John Harrington

present to act as foils.

Still, I am a little jealous of the person I was then.

(I guess that's a standard reaction to aging). I don't think

I'd mind living that part of my life over again...this IS an

option in fantasy literature, at least. I'd have a chance to

hit the issues again--harder, with the confidence potential

I'd then only partially reached. And I'd cherish my friends a

little more along the way, and be the great father and

husband I wasn't. In short, what I long for is to surmount

(which means climb to the top of) the great wall of

expectation which I created for myself, and become the

perfect person I now imagine I might have been...if granted

the power to go back in time, I'm sure I'd also be given the

super powers I'd need for my mission...

Actually, I don't waste much time longing for lost

opportunities. It comes in (decreasing) phases.

I suppose if I wanted to go back to Sacramento badly

enough I might get the Assembly Sergeant-at-Arms to hire me

as a docent (docents are persons who conduct tours of

museums, opera houses, and other places of public interest).

I think I'd be better used conducting tours of the Capitol

grounds than running the elevator or serving coffee to the

Powers.

"Ladies and gentlemen, in this park there are 2900

botanical species, mostly native Californian, but there are

specimens from all over the world. There, is the Junipero

Serra Fountain, and There, is a plot of rare and unusual

hybrid camelias, and over here's the bench my uncle the

elderly Senator Coombs used to rest on when he fed the

squirrels. He was 80 when he retired from the legislature.

Still, I am a little jealous of the person I was then.

(I guess that's a standard reaction to aging). I don't think

I'd mind living that part of my life over again...this IS an

option in fantasy literature, at least. I'd have a chance to

hit the issues again--harder, with the confidence potential

I'd then only partially reached. And I'd cherish my friends a

little more along the way, and be the great father and

husband I wasn't. In short, what I long for is to surmount

(which means climb to the top of) the great wall of

expectation which I created for myself, and become the

perfect person I now imagine I might have been...if granted

the power to go back in time, I'm sure I'd also be given the

super powers I'd need for my mission...

Actually, I don't waste much time longing for lost

opportunities. It comes in (decreasing) phases.

I suppose if I wanted to go back to Sacramento badly

enough I might get the Assembly Sergeant-at-Arms to hire me

as a docent (docents are persons who conduct tours of

museums, opera houses, and other places of public interest).

I think I'd be better used conducting tours of the Capitol

grounds than running the elevator or serving coffee to the

Powers.

"Ladies and gentlemen, in this park there are 2900

botanical species, mostly native Californian, but there are

specimens from all over the world. There, is the Junipero

Serra Fountain, and There, is a plot of rare and unusual

hybrid camelias, and over here's the bench my uncle the

elderly Senator Coombs used to rest on when he fed the

squirrels. He was 80 when he retired from the legislature.

"These many long and crisscrossing sidewalks were where

my youngest daughter Jane and her friend Erin used to skate

when they came for a day's adventure at the Capitol. And,

here's another bench: it's where Assemblyman Willie Brown,

later Speaker and now Mayor of San Francisco, used to study bill

briefings during noon recess of Ways and Means Comittee

meetings (which he then chaired). I assume that in the rain

and the snow he sat somewhere else--in a private corner of

his office where he could shut himself off for periods of

time, say. I know personally how effective Willie could be as

Chairman of Ways and Means--I remember he would occasionally

cut an author's bill presentation short and explain it to us

better, and more quickly than was being done. At every

committee meeting he conducted he had read all the briefs on

all the bills, knew the arguments for and against; sometimes

I'm sure he knew the bills better than the authors

themselves. I'd known him for 16 years when he was Speaker

and knew he was smart as a whip but many other people didn't

know him this well. Because Willie indulges in what one might

call 'street talk', and because some people equate

intelligence with use of the 'King's English', a few have

underestimated Willie Brown's ability.

Continuing the 'docent' bit:

"This grass-covered area with the single bench is where

I sat in the center of a large circle of students having a

pow-wow when they marched on the Capitol in 1969, protesting

the Vietnam war.

"And here, is Tulupis Grandeflora, or the Big Tulip Tree

I used to look at out of the window of my diminutive second

story "office-with-a-view" in 1967. And here--this good-sized

oak with spreading branches--is a very special tree. In this

tree my son David and his girl Robyn happened to have their

picture taken when they were up on a limb kissing on a hot

summer afternoon. David had visited with me that day and on

the way home he told me that he and Robyn had climbed a tree

and someone carrying a camera had come over, seeming amused,

and asked in a friendly way for their names. He didn't tell

me about the kissing or the photograph. I learned of that*

the next morning when Janet called me on the phone to tell me

David and Robyn's picture was on the front page of the Bay

Area's most prestigous newspaper, The San Francisco

Chronicle.

"These many long and crisscrossing sidewalks were where

my youngest daughter Jane and her friend Erin used to skate

when they came for a day's adventure at the Capitol. And,

here's another bench: it's where Assemblyman Willie Brown,

later Speaker and now Mayor of San Francisco, used to study bill

briefings during noon recess of Ways and Means Comittee

meetings (which he then chaired). I assume that in the rain

and the snow he sat somewhere else--in a private corner of

his office where he could shut himself off for periods of

time, say. I know personally how effective Willie could be as

Chairman of Ways and Means--I remember he would occasionally

cut an author's bill presentation short and explain it to us

better, and more quickly than was being done. At every

committee meeting he conducted he had read all the briefs on

all the bills, knew the arguments for and against; sometimes

I'm sure he knew the bills better than the authors

themselves. I'd known him for 16 years when he was Speaker

and knew he was smart as a whip but many other people didn't

know him this well. Because Willie indulges in what one might

call 'street talk', and because some people equate

intelligence with use of the 'King's English', a few have

underestimated Willie Brown's ability.

Continuing the 'docent' bit:

"This grass-covered area with the single bench is where

I sat in the center of a large circle of students having a

pow-wow when they marched on the Capitol in 1969, protesting

the Vietnam war.

"And here, is Tulupis Grandeflora, or the Big Tulip Tree

I used to look at out of the window of my diminutive second

story "office-with-a-view" in 1967. And here--this good-sized

oak with spreading branches--is a very special tree. In this

tree my son David and his girl Robyn happened to have their

picture taken when they were up on a limb kissing on a hot

summer afternoon. David had visited with me that day and on

the way home he told me that he and Robyn had climbed a tree

and someone carrying a camera had come over, seeming amused,

and asked in a friendly way for their names. He didn't tell

me about the kissing or the photograph. I learned of that*

the next morning when Janet called me on the phone to tell me

David and Robyn's picture was on the front page of the Bay

Area's most prestigous newspaper, The San Francisco

Chronicle.The chorus to David's father's day song goes: I think he'll follow in my footsteps (oh yeah) when I'm leading up the treetrail to the Future I.E. I might make it to the front page of the Chronicle sometime--or, a more general interpretation: that children, if they lead full lifespans, always lead the way into the future and are 'followed' in spirit by their parents. Alan and I had pioneered tax reform ever since we hit the Capitol in 1967. Our ideas were far more earthshaking than the traditional pablum served by Reagan, or for that matter than Jess Unruh's when he was Speaker. This year, we'd spent hours working on the details in our offices, and The Capitol Tamale Cafe, where we were headed for today's lunch meeting, had long since become one of our conference rooms. Back in 1967, Alan was 35, ten years younger than I. I had the same crewcut I'd had in lawschool, and wore relatively cheap storebought suits. My shirts were usually white, my ties conservative, though sometimes I had a pretty one. My favorite was sort of wooly-orange with white lines running through it. People would look at it, and admire it, and occasionally notice the small cloth label on it which said 'Fabric Content Unknown'. In 1967 Alan wore well-tailored expensive suits, the ultimate in conservative good taste. His shirts were always white. Anyone knowing us in 1967 might've said, "One comes from a cow county and the other from Beverly Hills, but they both look like the earnest young man applying for his first job."

And in 1969, only a couple years later, here I was 'sporting long sideburns', no longer wearing a butch--and, due to grow a beard in a couple more terms. At the time I went to the Senate, Alan had started having his hair styled and 'livened up'--actually, it looked good, once I got used to it. In 1974, Alan joined me in the Senate, and by this time we'd both gone whole hog and out of forty senators were the only two with beards.